Information has taken on a whole new meaning in the digital age, a time when sensitive data is either too easily accessible or not accessible enough. This issue of access to information encompasses fundamental human rights – specifically the freedom of speech as well as the right to privacy. Because it’s a primary means of maintaining transparency and accountability within government policies and decision-making in both the United States and around the globe, information is more valuable than ever to both government agencies and our individual lives. This guide takes an in-depth look at FOIA history and the importance of exercising your right to know.

September 28th marks International Right to Know Day. What began as a meeting between freedom of information organizations from 15 countries in 2002, has expanded to a global observance supported by more than 200 organizations worldwide. Each year, International Right to Know Day seeks to make people aware of the distinct rights they have to access government information that is essential to “open, democratic societies in which there is full citizen empowerment and participation in government.” Within the United States, those rights come in the form of the Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA.

July 2016, marked not only FOIA’s golden 50-year anniversary, a milestone in Americans’ rights to scrutinize government agency records, but also the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016. Together, they remind us that FOIA’s guarantee of access to information was not easily acquired – nor was it a legally binding right. In fact, FOIA’s very creation was highly controversial. And since it has passed, its implementation and execution have continued to present challenges of their own.

For more than 175 years, the United States relied on what was known as the 1789 Housekeeping Statute. As the U.S. Constitution does not specify policy or procedure for information sharing either among federal bodies or with the public, Congress’ 1789 statute authorized heads of departments to maintain records and to determine how those records would be used.

Although the legislation was considered simply a “housekeeping” measure for a growing nation, opponents of free access even today continue to invoke it in arguments to withhold information – even though a one-line 1959 amendment to the statute specifically states, “This section does not authorize withholding information from the public or limiting the availability of records to the public.”

As the growing nation continued to create agencies and departments, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt saw the need to once again establish some additional housekeeping rules through the Administrative Procedure Act. According to the act, federal agencies had to maintain records and make them “available to public inspection” – except for “information held confidential for good cause.” Fraught with loopholes, the act gave more cause to withhold information than to share it. However, it did require that agencies:

Post-World War II, however, conflict assumed new dimensions in the Cold War. Governmental secrecy increasingly frustrated journalists and the public alike. Open demand for information grew, spurred on by Harold Cross’ 1953 publication of The People’s Right To Know and ensuing congressional initiatives led by California’s Democratic Representative John Moss.

On July 4, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued a signing statement to edify Congress’ fresh, new Freedom of Information Act with limitations. Although his statement asserted that “a democracy works best when the people have all the information that the security of the nation will provide,” it focused heavily on the fact that “the welfare of the nation or the rights of individuals may require that some documents not be made available.” While reluctantly conceding the act as necessary, Johnson removed many of the act’s teeth exception by exemption. Even so, for the first time, a law had been written with the sole purpose of ensuring public access to federal agency records.

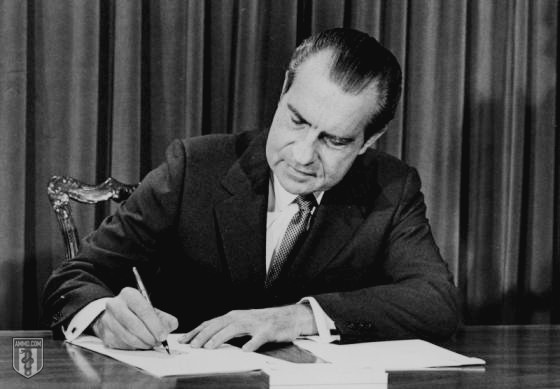

Less than a decade later, perhaps one of the greatest positives that resulted from the scandal of Watergate and the Nixon administration’s abuse of power was FOIA’s strengthening. As more and more details of secretive, inappropriate activities involving the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Central Intelligence Agency and Internal Revenue Service came to light, public distrust and demand for accurate information grew.

Less than a decade later, perhaps one of the greatest positives that resulted from the scandal of Watergate and the Nixon administration’s abuse of power was FOIA’s strengthening. As more and more details of secretive, inappropriate activities involving the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Central Intelligence Agency and Internal Revenue Service came to light, public distrust and demand for accurate information grew.

In answer, Congress drafted the FOIA Amendments of 1974 – not only passing them, but also overriding a presidential veto from then-President Gerald Ford. The amendments became law on November 21, 1974, establishing:

Two years later, as acknowledgement that most decision-making occurs behind closed doors, the Government in the Sunshine Act of 1976 sought to open them. Under the act, any meeting involving a quorum of board or commission members must be placed on the Federal Register seven days in advance and must allow interested members of the public to attend. However, it, too, contains exemptions and issues of interpretation that continue to obscure the intended transparency, especially for journalists and the media, who often are the first to inform the public of new or pending changes within our government.

By the 1980s, executive orders concerning the classification and handling of sensitive intelligence information were nothing new. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Nixon and Carter had all issued ones of their own. However, President Ronald Reagan’s Executive Order 12356, effective August 1, 1982, gave classifying authorities considerable leeway in being able to withhold information on the basis of preserving national security. Among many other exemptions, of particular note were instructions that:

Along with concerns about national security, the War on Drugs marked the 1980s. While addressing an America struggling with drug addiction by tightening mandatory sentencing guidelines, Congress’ Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 under the Reagan administration also amended FOIA. Its Subtitle N broadened the exemptions for access to law enforcement records, especially information regarding informants or active investigations. It also categorized FOIA requests and fee structures by purpose – commercial, scholarly or in public interest – making fee waivers much more difficult to obtain.

In an effort to simplify the FOIA process, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Executive Order 12958 in 1995, setting forth criteria that would allow hundreds of thousands of documents that were more than 25 years old and of “permanent historical value” to be declassified. Setting a new tone, the order stated, “If there is significant doubt about the need to classify information, it shall not be classified.”

With government agencies backlogged with requests for information and the World Wide Web a rapidly expanding reality, President Clinton also signed into law the Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments of 1996. The amendments sought to bring federal agencies into the electronic age and make information readily accessible. It mandated sharing of federal agency information through webpages and reading rooms, but doubled agency response times from 10 days to 20. The hope was that accessibility to government-provided data from any location through the Internet would substantially both reduce the number of requests for information and increase transparency.

The threats that September 11, 2001, and the ensuing conflict presented to national security altered – and in some cases even reversed – prior initiatives to make information more accessible. Policymakers viewed the sheer volume of information as well as users on the Internet and their global reach far beyond U.S. domestic control as a vulnerability.

The threats that September 11, 2001, and the ensuing conflict presented to national security altered – and in some cases even reversed – prior initiatives to make information more accessible. Policymakers viewed the sheer volume of information as well as users on the Internet and their global reach far beyond U.S. domestic control as a vulnerability.

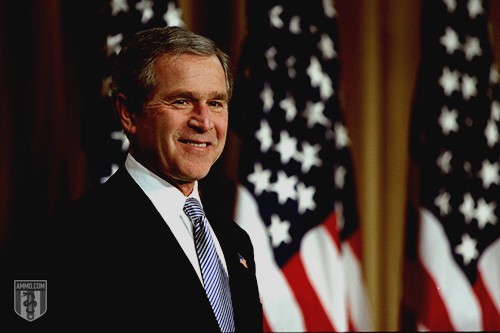

Under President George W. Bush’s administration, a number of congressional actions coupled with executive orders once again pushed the FOIA pendulum to more restrictive limits:

As 2007 drew to a close, Congress passed the OPEN Government Act of 2007, and President George W. Bush signed it into law on December 31st. The first sentence identified it as an act “to promote accessibility, accountability, and openness in Government by strengthening section 552 of title 5, United States Code (commonly referred to as the Freedom of Information Act).” It acknowledged that “disclosure, not secrecy, is the dominant objective” and that “in practice, the Freedom of Information Act has not always lived up to the ideals of that Act.” In that spirit, the act:

To learn more about the FOIA today and tips for how to submit your own request for information continue reading Right to Know: A Historical Guide to the Freedom of Information Act at Ammo.com.