The Civil War (1861-1865) was nothing less than a revolutionary reorganization of American government, society, and economics. It claimed almost as many lives as every other U.S. conflict combined and, by war’s bloody logic, forged the nation which the Founding Fathers could not by settling once and for all lingering national questions about state sovereignty and slavery.

The postwar period, however, was one of arguably greater turmoil than the war itself. This is because many men in the South did not, in fact, lay down their arms at the end of the War. What’s more, freedmen, former slaves that were now American citizens, had to take defensive measures against pro-Democratic Party partisans, the most famous of whom were the Ku Klux Klan.

America’s militia has existed for a number of purposes and has exercised a surprising number of roles over the years. But at its core, it’s a bulwark of the power of the country against the power of the state. In Early American Militias: The Forgotten History of Freedmen Militias from 1776 until the Civil War, we covered the historical roots of the milita. Below is the modern history of the militia following the Civil War, and how unforeseen changes which started during Reconstruction have set the stage for the contemporary movement of Constitutional citizens militias.

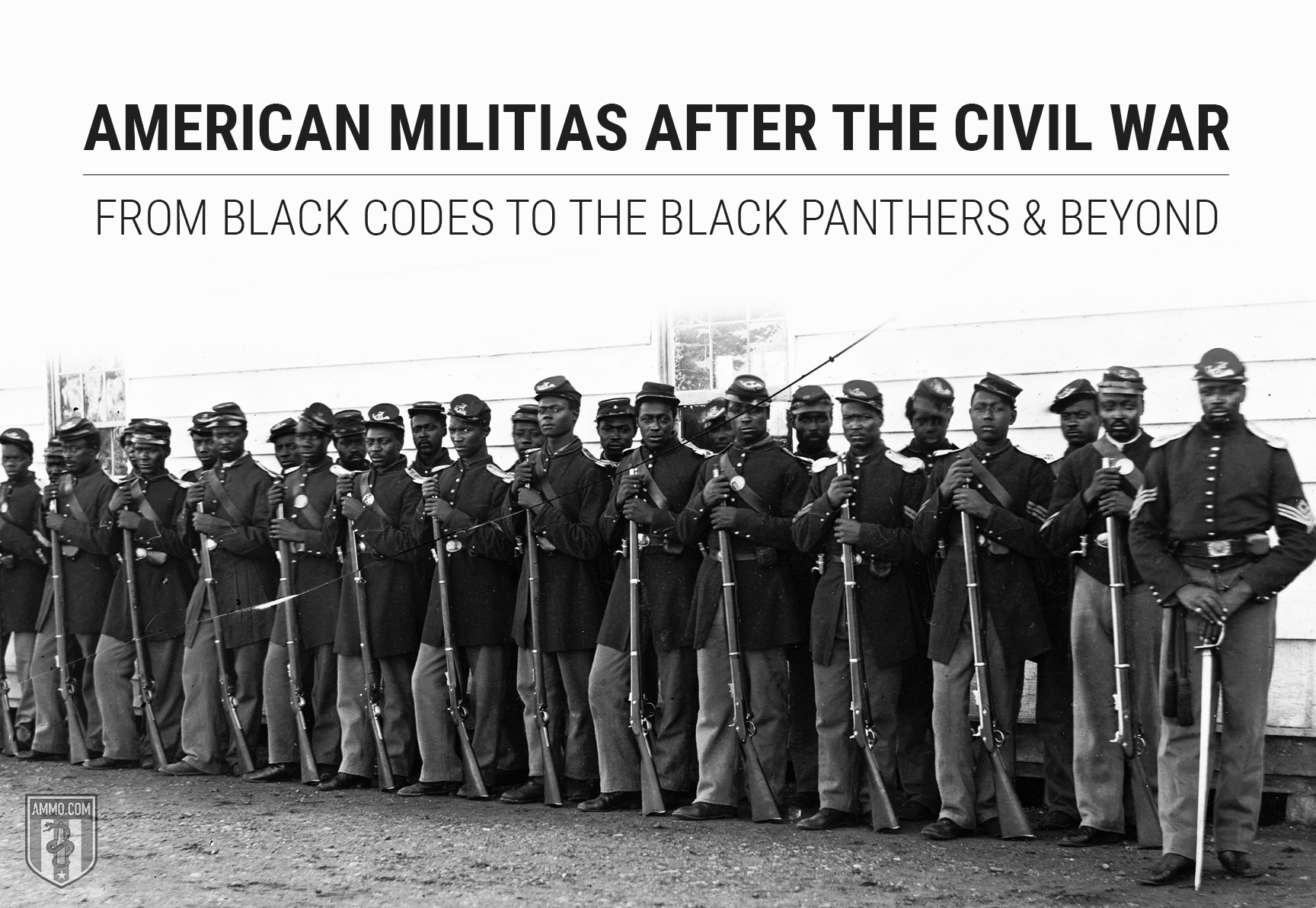

The Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) is one of the most fascinating – and violent – periods of American history. After the defeat of the Confederate States, the United States Army took direct control of the quelled rebel states. Elections were eventually held and Republicans won every state, with the exception of Virginia. The state governments then organized militias, which were comprised of a majority of black men.

To say that there was racial tension in the former Confederate states would be an understatement. Not only was the South under continued military occupation, but they were also being occupied by their former slaves, now armed by what was until very recently a foreign power. The white population of the South responded to what they considered to be an attack on them and their rights by organizing militias of their own, despite the fact that this was prohibited by law. In fact, postbellum laws on militia organization prohibited drilling, parading, or organizing.

Fears among Southern whites were not unfounded, nor without precedent. The 35th United States Colored Troops went house to house in Charleston confiscating firearms. Black troops were known for looting and rioting during the final days of the war. The 52nd United States Colored Infantry sacked the Vicksburg plantation belonging to Jared and Minerva Cook, where it is believed some of them had been slaves. They confiscated the plantation’s guns at the point of a revolver, shooting both Cooks, killing Minerva and seriously wounding Jared.

A correspondent writing at the time spoke of the palpable fear of the white population: He believed that a massacre of the entire white population was impending. This anxiety is what led to the so-called “Black Codes” of the postwar era, which included tight restrictions on the weapons that could be owned by free blacks – if any at all. Some laws even restricted blacks from owning knives.

It’s worth noting that black veterans of the time were armed quite well. Not only did many keep their service weapons after the war was over, but they were also in possession of weapons claimed as war prizes. The average black citizen of the time, however, wanted only arms for self defense. Indeed, the mutual feeling of uneasiness in the postwar South seems to have a solid foundation for each group. How comfortable would most people feel with an occupying army of hostile former slaves? And how comfortable would most former slaves feel surrounded by recent insurgents?

These independent white militias were effectively a form of guerilla resistance against reasserted Union control in the South. Activity on either side tended to peak around the time of elections, suggesting that each was engaged in a campaign of intimidation against the other.

Some of the first anti-gun control movements in the United States were among freed blacks seeking to keep and bear arms for their own protection against the white independent militias. The names are familiar to most Americans: The Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camelia, The Red Shirts, The White League, The White Brotherhood. These white independent militias have been called by George C. Rable the “military arm of the Democratic Party.” Many blacks who had no intention of firing a shot in anger wanted a weapon simply to keep themselves and their families secure in the face of armed terrorist gangs seeking to circumvent the Reconstruction.

However, winners, as they say, write the history books. The Southern side of the argument is that the Union League, a Northern organization dedicated to patriotism, unionism and opposition to “Copperhead” Peace Democrats was, by the end of the war, organizing in the South. While less known than the above-mentioned groups, the Union League (also known as the Loyal League) was certainly not innocent of violent assaults, murder and rape. This made the most innocent of Union League members a target for Southern, pro-Democratic groups.

In the battle between the largely black, pro-Federal and Republican groups and the overwhelmingly (if not exclusively) white, pro-Southern and Democratic groups, the latter ultimately won the day. Reconstruction was ended as part of a bargain to secure Republican Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency in 1876. The North in general, and the Republican Party in particular, was tired of dealing with the Southern issue. Northern sympathies for black troubles were tepid to nonexistent a decade after President Andrew Johnson declared a formal end to hostilities.

Beyond the national political loss of will to continue Reconstruction, there are other, more intangible factors in play. White independent organization was stronger than the black, federally backed organizations. What’s more, while the black population was afraid, the white population was mad with desperation. Blacks in government, armed with the backing of federal power seemed to them no less than an inversion of nature and an existential threat to all white Southrons.

With federal troops and backing withdrawn from Reconstruction, the stage was set for Jim Crow and a rollback of many of the social gains blacks enjoyed during this era.

While the popular vision of the post-Reconstruction Era is one of constant terror from pro-Democratic paramilitary groups such as the KKK, this is inaccurate. The Knights of the White Camelia, an upper-crust organization, had largely ceased to exist by 1870. Nathaniel Bedford Forrest ordered the Klan disbanded in 1869, increasingly concerned with their lawless behavior and his inability to control it. President Grant’s Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871 were squarely designed toward dismantling what remained of the Original Klan. The White League, perhaps the most militant of the group, disbanded in 1876, seeing their aims as largely accomplished. The Red Shirts lingered on until 1900, but their efforts were primarily around voter intimidation at election time, rather than a constant campaign of harassment, terror and intimidation.

The point is not to soft pedal or minimize the attacks against blameless black civilians during and after the Reconstruction Era. However, the white paramilitary groups were largely inactive for the simple reason that the Democratic Party state governments were accomplishing most of their goals through the rule of law.

Continue reading American Militias after the Civil War: From Black Codes to the Black Panthers and Beyond at Ammo.com.